‘Funny, wise and really quite moving – a tour de force’

Humphrey, a retired academic, considers himself to be a failure – at sex, at love, at life. He is acutely sensitive to noise and finds the twenty-first century bewildering. He expresses his disappointment at bi-weekly meetings with his cronies at The Seven Stars and in wrangling with his next door neighbour about her cat, Aristotle.

Seventeen year-old Jack is going off the rails. He is full of anger at the cards life has dealt him. He feels he has no future. He vents his anger in acts of vandalism and deliquency.

When Jack trashes Humphrey’s garden it is the beginning of an unlikely friendship in which both stand to gain. But when Humphrey is accused of a crime he did not commit, Jack cannot be found. Is this misfortune or a deliberate betrayal?

Ian Thomson has written a nuanced novel which is by turns hilarious and poignant. While Martin, his debut novel, was about revenge, Humphrey and Jack is about redemption. Once again his agile prose will forbid you to put it down.

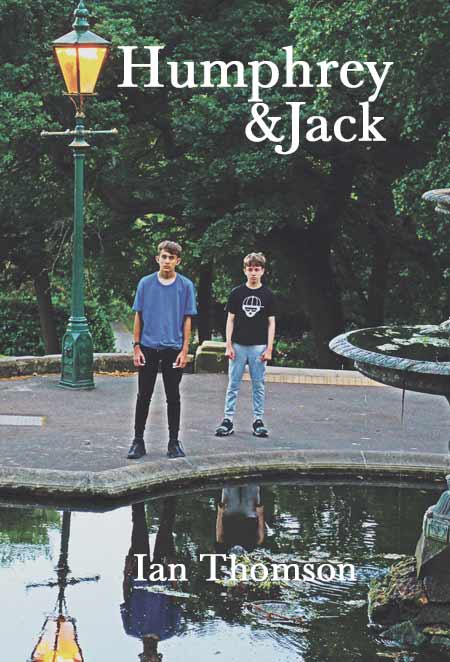

Cover photograph by Helen Brace.

An excerpt from Humphrey & Jack

Humphrey loathed cats. To be fair, he had a suspicion that he might be allergic to them and that a chance encounter could result in a rash and hideous sneezing fit. However, he reserved a particular detestation for this cat – a cat which he sincerely believed lived only to annoy him.

There had been the occasion when it had left a mangled partridge on his doorstep and Humphrey had nearly trodden on the carcass from which a cloud of nasty flies arose and settled. Recently, it had taken to parading back and forth along the terrace at night, turning the security light on and off and waking him up. He had seen the animal do it. Padding across the paving with its tail in the air, flooding his bedroom with orange light and returning when it went out. Finally, there had been the occasion on an insufferably hot night last August when Aristotle had got into his downstairs bedroom and sat on his head whilst he slept. Naturally it had frightened the hell out of him and he had grabbed the thing and flung it back out of the open window. He had not slept again that night.

Humphrey shifted slightly in his seat. Simultaneously, the blackbird flew off in his curve to the rhubarb and the cat streaked across the lawn and under the leaves.

‘Aristotle, NO!’

Humphrey rose to his feet, knocking over his Martini.

He was relieved to see that almost immediately the blackbird and his mate had flown out from the other side of the rhubarb patch and both of them had glided into an azalea bush on the other side of the garden hotly pursued by the cat which was now crouching low and stalking towards the bush.

‘Aristotle, sod off! Go on! Shoo!’ Humphrey bellowed, trying to pelt the cat with olives which fell far too short.

‘Leave them alone, Aristotle! Bugger off!’

He was suddenly aware that anyone in the public park which lay just beyond the low hedge at the bottom of the garden might have looked up and seen a sixty year old man waving his arms about and seemingly swearing at a Greek philosopher who had been dead for two and a half thousand years.

The cat, however, was blithely ignoring him and lay on the grass, head on front paws, staring into the bush.

There was nothing for it but for him to go down the stone steps on his creaking knees and chase the creature away. He picked up a stone on the way and threw it. Bingo! It hit Aristotle on the haunch and the cat turned with a yowl and sped in the opposite direction to the fence which ran between Humphrey’s garden and his neighbour’s. There, it looked back at Humphrey with a baleful stare, and then slipped like a black liquid through the narrow gap in the palings.

As Humphrey slowly climbed the steps back up to the terrace, the noise started up.

First there were the yippy dogs. Humphrey did not despise dogs as much as he did cats but he had no time for the little varieties with their high-pitched yip-yip-yip which set his teeth on edge. He abhorred these Yorkshire terriers and King Charles spaniels and dachshunds and corgis and other little rat-like lap dogs that no grown man should be seen with in public. Yet here they were, with their masters, out for their evening walk, and as soon as they were let off the leash, off they went, chasing each other in frenzied circles, and yipping away till Humphrey physically felt the noise as a tautening of the skin across his temples.

Then there was the screaming girl.

At the bottom of the park, near Prior Ingham’s Road, out of sight of Humphrey’s house except from upstairs, there was a children’s playground. Now, the sound of children playing didn’t unduly upset him. He wasn’t an ogre. The swings and slide and climbing frame were sufficiently distant for their cries to come to him on the evening breeze like childhood memories, dimmed and subdued by time.

Apart from the screaming girl.

He assumed it was a girl because no self-respecting boy would make such a racket and then keep it up, sometimes for almost an hour at a time, every blessed evening. It was an attention-seeking scream, a phoney distress scream, a diminutive diva scream. It made him want to find the child and say: ‘I’ll give you something to scream about’, and then strangle her so she couldn’t.

As usual, a game of football had started up near the bandstand and local oiks were uttering their oafish cries with every thump of the ball.

Lads on motor bikes with their silencers removed were roaring up and down Prior Ingham’s Road.

A neighbour had started up a strimmer.

Worst of all, the gang with the boom box were back. The amplified music with its thudding bass and moronically banal lyrics invaded the evening and took possession of it completely

Humphrey righted his Martini glass on its little tray and went back inside the house.

‘Just one Martini,’ his doctor had said but Humphrey set about mixing another. After all, he had spilt his first one. It’s true that there had been very little left in the glass but Humphrey was quick to persuade himself that he deserved another because of the din outside. He could still hear the banging bass rhythm in the kitchen even though it was at the other side of the house. He could actually feel the vibrations. They seemed arrhythmic and were very unsettling. He would have to tackle these youths, he thought. He could not endure this racket every night.

A second Martini led to a third and he was feeling defiant and courageous when, at about half-past nine, he set off down the garden with a walking stick to berate these selfish hoodlums over the low hedge.